Tinker, the man

'But is it good, Brandon? Is it good?'

The veteran TV writer and showrunner Henry Bromell once sketched a family history of quality TV. After starting at the bottom with The Sopranos, The Wire, and Mad Men and a handful of other recent shows, he quickly moved upward, along a spreading spiderweb of connections that filled the page. At the top, alone, he wrote on name in capital letters: Grant Tinker.

Four decades after he left an executive position at 20th Century Fox Television to form MTM Enterprises – named for his second wife, Mary Tyler Moore, and created to produce her eponymous sitcom – Tinker remains that rare, if not unique, creation: a television executive revered by television writers. If you know anything about these types, you may be able to guess that writers loved Tinker because Tinker believed in the importance of writers.

He became known as an indefatigable advocate for his writers and a tireless defender of their work against meddlesome networks. Both John Falsey and Joshua Brand – who would create St Elsewhere at MTM – remember sitting in Tinker’s office, listening to one side of a phone conversation with NBC Entertainment president Brandon Tartikoff, who was apparently unhappy with the ratings performance of a particular show. “But is it good, Brandon?” Tinker said over and over. “Is it good?”

Of course Tinker, for all his genuine appreciate for and support of writers, wasn’t running a nonprofit artists collective. He believed that his approach was not only good for art, but good for business. This was the era of Fin-Syn, the Financial Interest and Syndication Rules, enacted in 1970, that among other things prohibited the big three TV network from producing and owning their own programming.

Until their repeal in the 1990s, the Fin-Syn rules bestowed enormous power and profit on independent producers, who maintained ownership over their programs and syndication rights. Not only would happy writers produced profitable programs, Tinker believed, they would also attack a steady stream of more good writers. He proposed a showbusiness axiom – “The best creative people love to work with other best creative people” – and described the ensuing “magnet effect” that made recruiting talent surprisingly easy.

In this, Tinker’s studio provided a blueprint for what HBO would become in the late 1990s and early 2000s. MTM’s offices in Studio City became the place writers wanted to be – not necessarily because it was where they’d get the most money, but because they’d have the freedom to do good work.

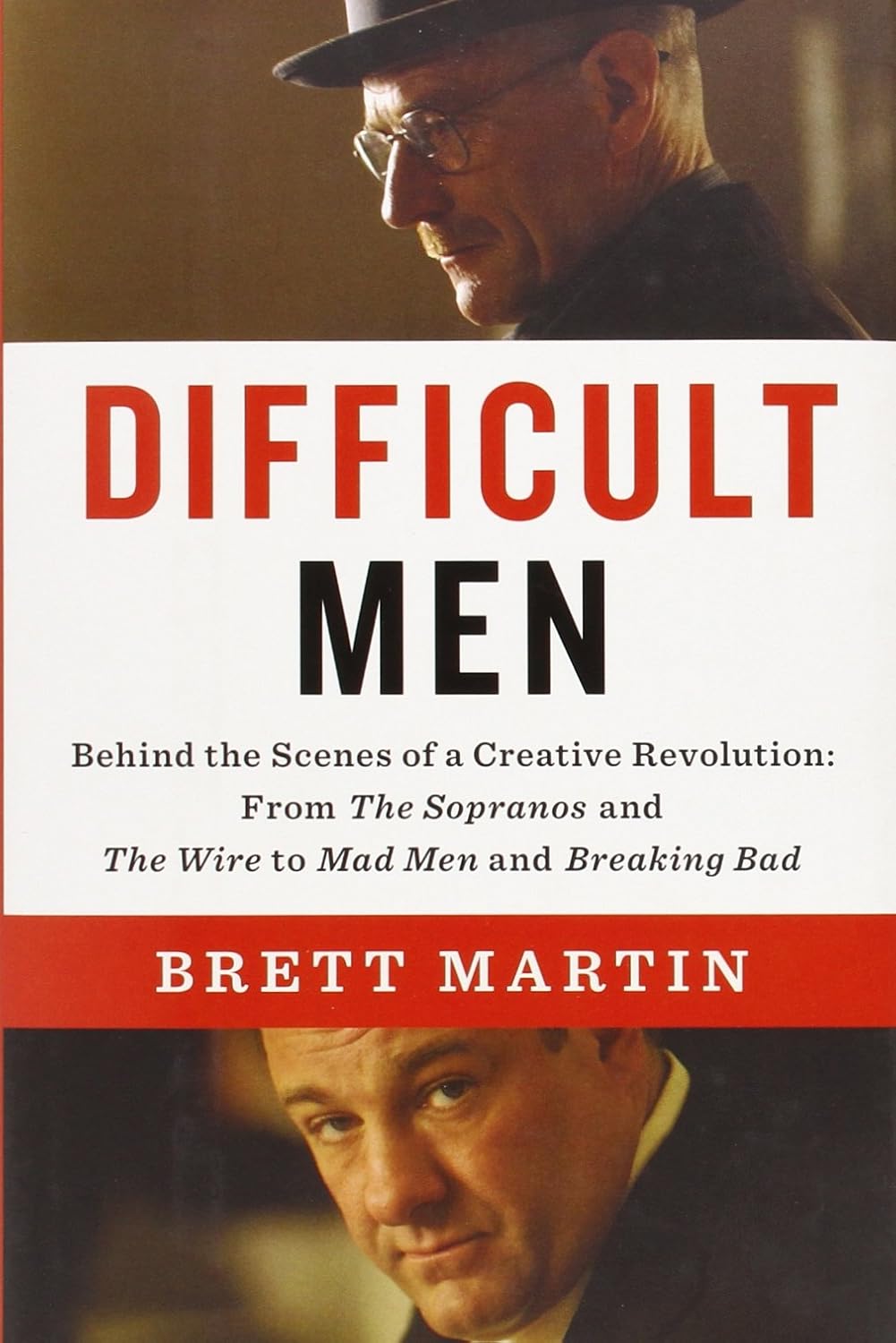

- Taken from Difficult Men, published by Penguin