Hot hot heat

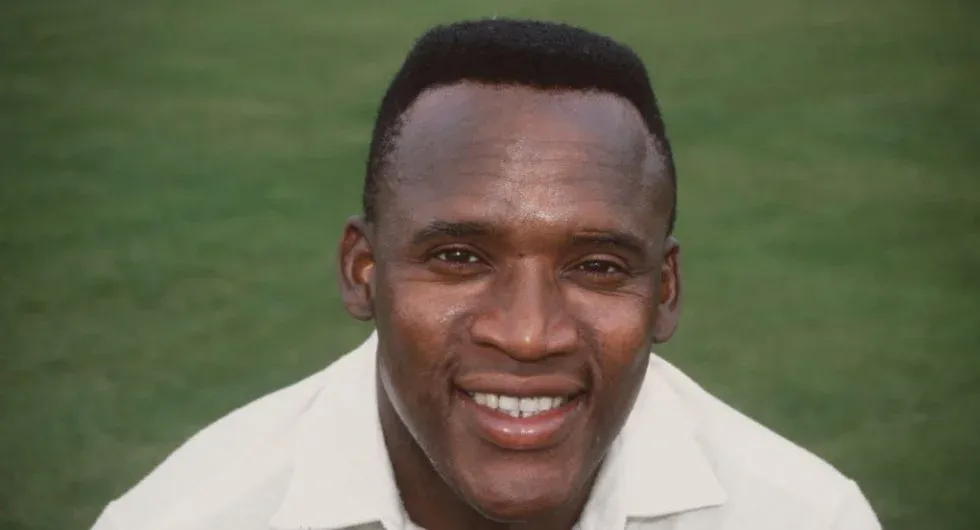

A year before he laid waste to South Africa at the Oval, Devon Malcolm bowled an even faster spell to beat Australia

Devon Malcolm bowled the fastest spell of his career at the Oval. This much we know, or rather we think we do. Nobody of sound mind would dispute that Malcolm’s awesome performance against South Africa was the greatest of his career, but for pure, rhythmic speed it was surpassed by a short Sunday-evening burst against Australia on the same ground a year earlier.

Malcolm’s nine for 57 against South Africa has defined his career, even his life, and is proudly referenced in everything from his number plate to his email address. Figures of 2.2-2-1-0 are less eye-catching, and less number-plate friendly; yet he regards those 14 balls in the gloaming as the quickest he ever bowled.

Malcolm, making his first appearance of the series, put the wind up the Australians throughout the match and helped England to their first victory of a largely miserable decade in Ashes cricket. We did not realise it at the time, but his performance was an obvious prequel to his demolition of South Africa a year later.

Australia were 4-0 up going into that final Test in 1993, having administered the usual towelling. England had been through seven seamers in the series – nine if you count Graham Gooch and Graham Thorpe – and turned to all-new, all-old seam attack of Malcolm, Angus Fraser and Steve Watkin, none of whom had played in the series. Fraser, because of injury, and Watkin had not played a Test since 1991.

Australia’s top six of Michael Slater, Mark Taylor, David Boon, the Waugh brothers and Allan Border – most of them grizzled, merciless punishers who could have come straight from the set of a Western - had enjoyed a summer of plenty. At Lord’s they made 632 for 4 declared; at Headingley they saw that and raised it to 653 for four. In the first five Tests they averaged 61 runs per wicket, an Ashes record. Then, in the sixth Test, Malcolm, Fraser and Watkin dismissed them for 303 and 229 – it would have been fewer but for tail-end resistance in each innings – and gave England a 161-run win, their first over Australia for seven years and their first against anyone for a year. The three seamers shared all 20 wickets. It was the first time they ever played together for England, and the last.

The match was Mike Atherton’s second as captain an included what felt like breakthrough contributions from Graeme Hick (a regal 80, batting at No3, on the first day) and Mark Ramprakash (a maiden Test fifty). Atherton’s plan to make a long-term investment invest in players of class and character did not survive the appointment of Ray Illingworth at the start of the 1994 summer. But for a moment in time, it seemed like England might just copy Australia’s ascent from rock bottom.

Central to that flight of fancy were Malcolm and Fraser, who had bowled splendidly together before Fraser’s hip injury on the 1990-91 Ashes tour. At times they were not so much good cop/bad cop as good length/bad length; but when Malcolm was anywhere near his best they complemented each other perfectly.

“I had a very good tour of the Caribbean in 1989-90 with Angus Fraser,” says Malcolm. “My remit was to try to rough them up - even the mighty Viv Richards. Angus was a brilliant line-and-length bowler; we did work well off each other and it was a shame he got injured.”

At the Oval in 1993, Fraser took eight wickets and was Man of the Match, a fairytale return for a cricketer who could barely have been more popular. Malcolm’s figures of three for 86 and three for 84 do not look spectacular, yet the way in which he unsettled the Australians changed the mood. “After a summer in which the Australian batsman have been in more danger of being knocked over by a handful of confetti,” wrote Martin Johnson in the Independent, “their first exposure to some high velocity bullets produced a feeling not too far removed from glee here yesterday.” Only 1990s English cricket fans could engage in such rewarding schadenfreude at a time when their team were 4-0 down.

It was neatly symbolic that Malcolm dismissed each of the top six in the match, as he ripped them all from their comfort zone. A year later, before the return series ion Australia, Mike Atherton said Steve Waugh had been “wetting himself” while Malcolm set about him in the first innings. It’s a shame the strength of Slater’s bladder on the fourth evening of the match is not recorded in Wisden. When Australia started their second innings, the light was poor and the crowd ravenous. In 2.2 overs before the weather intervened, Malcolm gave a Slater a ferocious working over. At one stage he had only one fielder in front of the bat – and that was short leg. Slater was hit in the arm, stomach and almost the face, and the dancing feet that had served him so well in his debut series were now moving towards the square-leg umpire.

“I tell you what, the ball was absolutely zinging through!” says Malcolm. “When the umpires took us off the field for bad light, I could see the relief on the faces of the opening batters. When Dean Jones came to Derbyshire in 1996, he said that was the most reluctant he has ever seen Michael Slater to get forward.”

As with all fast bowlers, there is no simple explanation why Malcolm should have hit top gear at that moment. “Sometimes you try to bowl quick and you can feel the strain on your body – the shock on your back or through your legs,” he says. “But when you’ve got a good rhythm you don’t feel the strain. Your run-up is fine: you’re hitting the crease, you don’t have to look down or worry about bowling no-balls, and you’re following through straight … it makes it so much easier on the body. You feel as if you have got so much more to give.”

Malcolm’s overall record against Australia was not great – 42 wickets at 45 – but it’s no coincidence that he took more wickets than anyone in England’s Ashes victories of the 1990s. A volcanic new-ball burst, in which he reduced Australia to 23 for four, set up the famous win at Adelaide in 1994-95. He was also desperately unlucky at times, most notably at Perth in 1994-95: he broke Slater’s thumb, had an absurd number of catches dropped and ended up with match figures of two for 198. “I knew,” says Malcolm, “that they respected the pace I bowled at.”

That observation is backed up in Steve Waugh’s autobiography. “I always found facing Devon Malcolm a difficult assignment, largely due to his unpredictability and genuine pace. He was a match-winner, but throughout his career he didn’t fit the mould required by the English selectors. He was poorly managed, plagued by inconsistent selection and hampered by team strategies. Australia, as a team, breathed a sigh of relief whenever a steady medium-pacer was picked in front of him … On his day, he was as quick as anyone I’d ever faced.”

His day often came in SE11. In the early 1990s, the Oval was an English version of Perth – a magnificent, rock-hard pitch prepared by Harry Brind that produced ceaselessly exciting cricket. Malcolm took 27 wickets at the Oval – his next best on a single ground was 15 at Lord’s – and 21 of those came in three Tests from 1992-94 when the surface was at its quickest.

“The pitch was hard and fast but it was also one of the best batting pitches because the bounce was so consistent – there were a lot of runs scored,” says Malcolm. “The harder you hit the pitch, the more you got out of it. Most games I played there I did pretty well.” Even on his ODI debut, against New Zealand at the Oval, he was Man of the Match with figures of 11-5-19-2.

His good form at the ground started to perpetuate itself, and his enthusiasm is such that, even in his mid-50s, he still talks about it in the present tense. “I just find it a very, very special place to play cricket,” he says. “The crowd, man: it’s unbelievable. They lift you so much. Maybe it’s those old gas drums in the background, but I’m just so fired up any time I play there, even in county cricket. Some players have favourite grounds or favourite opponents. It’s like Brian Lara: why on earth did he break the world record twice at the Recreation Ground in Antigua?”

Malcolm has a theory about his own favourite ground. “I don’t know if there’s something buried in my psyche that helped me to do well at the Oval. One of my boyhood heroes was Michael Holding and I used to watch a video of him bowling England out at the Oval back in 1976. I’ve still got it somewhere; I’ll have to try and get it on DVD as it’s still on Betamax! As a young boy growing up in Jamaica you’d always hear about Michael Holding. His best figures were at the Oval and my best figures were at the Oval too. That makes me proud and probably explains why the Oval is so special to me.”

The downside of that is that, for much of his career, Malcolm was almost seen as an Oval specialist. In four consecutive seasons from 1992-95, he was dropped at the start of or during the summer and then recalled for the last Test at the Oval. The common lament over the erratic selection policies of the 1990s focusses on unfulfilled batting talents like Graeme Hick and Mark Ramprakash. Yet the bowlers were even more susceptible to being left out before they’d had a trot in the side, never mind a run.

Malcolm missed the Test after his debut because of injury but then played 17 matches uninterrupted before he was dropped in 1991. After that, the last 22 Tests came over six years and in 13 different spells. On a couple of occasions his absence was caused by injury, most notably when he contracted chickenpox at the start of the 1994-95 Ashes tour, but mostly it was selectorial whim. “It was one game on, one game off,” he says. “All I needed was a bit of confidence and for the management to say, ‘Dev you’re going to be playing the whole of this series.’ I remember when we played the West Indies at Headingley in 1995. At the end of the game, Brian Lara shook hands with me and said, ‘See you in the next Test match.’ And I said, ‘No you won’t. I bet you I won’t be picked for the rest of the series, except maybe the last Test match.’ And that’s what happened. You can’t be part of a team expected to win and feel that way.

“I’ve been given the tag of being erratic. When you bowl at express pace as I did, you only have to be a little bit off line before it to goes wrong. Fast bowlers are match winners. My confidence could be up and down, especially in Test cricket. But if I was that erratic, I don’t believe I’d have taken over 1000 first-class wickets. I was an attacking bowler!”

We will never know how his career would have panned out in a parallel universe, or how often he might have been able to enter the zone as he did so terrifyingly against South Africa in 1994. “I only realised how loud the crowd cheered my every stride to the crease, when I saw the highlights after the game,” he says. “All my focus was on the batsman. I couldn't hear a thing. It was total silence from the moment I turned at the end of my mark; I could only hear my foot fall. I was so focussed. I was somewhere else.”

He was, but being at the Oval sure helped him get there.

An earlier version of this article appeared in the Nightwatchman